Generating strings

We’re going to generate alphanumeric strings of a given length, following certain patterns. These strings will be used as passwords for the battered robot fleet, which was easily attacked due to weak passwords - factory defaults or ones easily cracked by brute force.

Length and combinations

Before we proceed, let’s analyze how a password - really just a simple string of limited length - can become strong protection against a brute-force attack if it introduces enough variety.

This type of attack attempts to guess the password by repeatedly testing different combinations, often using dictionaries or known patterns.

To begin with, let’s imagine something that really shouldn’t exist as a password: a single decimal digit from 0 to 9. If you guess the number, you’re in.

As you’d expect, guessing the password in this case would take between 1 and 10 attempts. That’s not secure at all.

Now let’s imagine a password made of a 4-digit PIN. How many possible combinations are there?

10 x 10 x 10 x 10 = 10.000

That’s a bit better, but still not enough if we automate the process to test combinations.

What happens if we go further?

If we use 6 digits and only numbers:

10⁶ = 1000.000

If we combine uppercase letters, digits, and at least one special character:

- 26 uppercase letters

- 10 digits

- 10 special characters (e.g., !@$%#*_-^|)

That gives us 46 possible glyphs per position:

46⁸ = 2 * 10¹³ possible combinations.

If the strings are generated randomly and avoid matching real words, the time required to guess a password by brute force can range from impossible to several years, depending on the attacker’s resources. And that’s just for a single password.

The Vulnerability

There are thousands of robots...

The AI from the ancient terminal said the robots were the virus’s entry vector into the system through their proximity interface. The vulnerability lies in the fact that all the robots share the same factory-set access PIN (123456) and the same 128-bit internal key used to encrypt communications.

The virus was planted knowing both in advance.

Every time the core system tries to recover, the infected robots bring the virus back.

The solution is to generate a different 128-bit key (16 bytes) and a new PIN for each robot. The new keys won’t repeat or follow any sequential pattern - meaning that even if an attacker manages to guess one password, they still have all the others left to crack. Even if they try in parallel, good luck with their brute-force superalgorithm, because it’ll be overheating for a very, very long time.

The AI in the old terminal can send the overwrite command for keys and PINs but it just can’t generate them fast enough.

As soon as the keys and new PINs are implanted in the robots, they’ll be temporarily disconnected, and the global system will be able to attempt a restore from a backup.

The virus lives in runtime.

The keys, being random, must be generated at runtime since they aren’t deterministic.

Generating PINs

We can prepare the new PINs at compile time, since they’re just numbers in a limited range (with 6 digits, from 000000 to 999999), so we can make a deterministic selection.

Even if the PINs are deterministic, they shouldn’t be easy to guess - so we’ll use a simple formula that’s not immediately obvious.

pins.zig |

|

const std = @import("std"); const print = std.debug.print; // get the pin for a given index fn get_pin4index(n_x: usize) usize { const n_a = n_x + 1; // pentagonal number formula limited to 6 digits return (n_a * (3 * n_a - 1)) / 2 % 1_000_000; } pub fn main() void { // variable defined at compile time comptime var a_pins: [1000]usize = undefined; // block executed by the compiler comptime { @setEvalBranchQuota(2000); for (0..a_pins.len) |n_i| { a_pins[n_i] = get_pin4index(n_i); } } // runtime loop to print // the pins generated at compile time for (a_pins[0..10].*, 0..) |n_pin, n_i| { print("a_pins[{}]: {}\n", .{ n_i, n_pin }); } } |

|

$ zig run pins.zig |

|

a_pins[0]: 1 a_pins[1]: 5 a_pins[2]: 12 a_pins[3]: 22 a_pins[4]: 35 a_pins[5]: 51 a_pins[6]: 70 a_pins[7]: 92 a_pins[8]: 117 a_pins[9]: 145 |

We generate 1000 PIN codes using a mathematical formula that produces a sequence of numbers. It's the formula for pentagonal numbers.

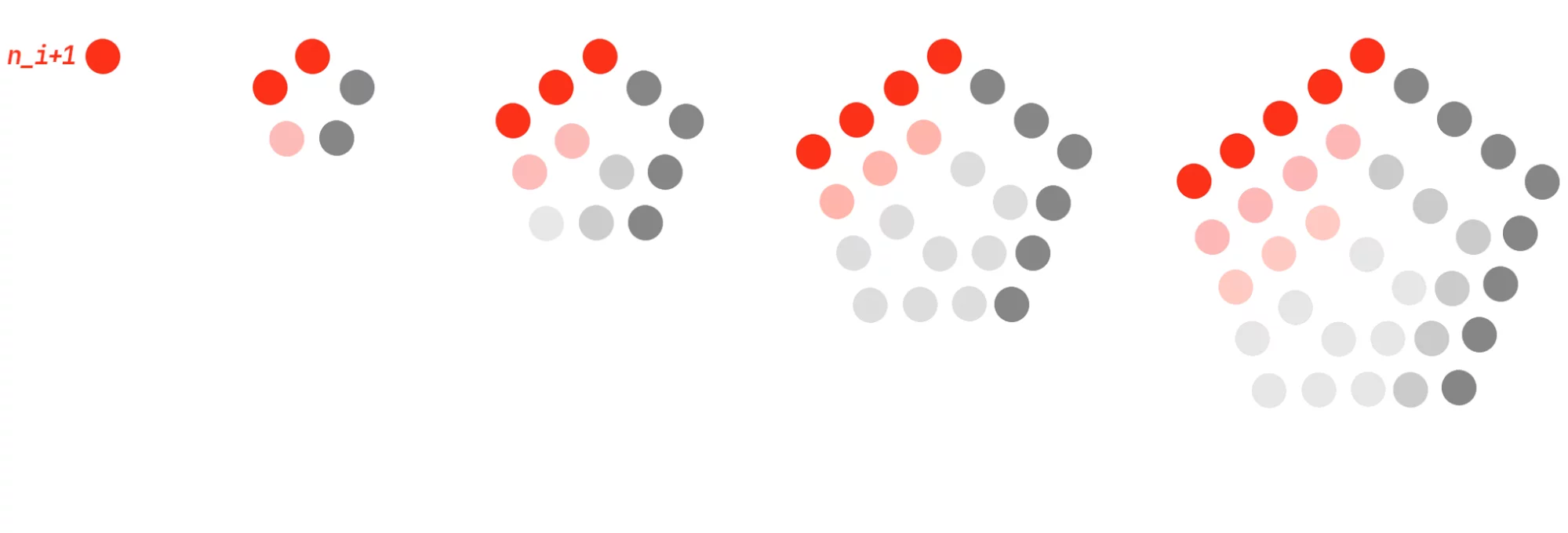

The nth pentagonal number is calculated like this:

The numbers generated this way follow the sequence: 1, 5, 12, 22, 35 …

Pentagonal number progression

|

Each number shows how the pattern grows as new layers are added to the pentagon. They're like triangular or square numbers, but with five sides. This series often appears in combinatorial theory.

We use the comptime keyword to define compile-time variables and entire blocks that will be executed during compilation.

|

// compile-time variable comptime var a_pins: [1000]usize = undefined; // block executed by the compiler comptime { @setEvalBranchQuota(2000); for (0..a_pins.len) |n_i| { a_pins[n_i] = get_pin4index(n_i); } } |

Not every block of instructions can be executed by the compiler. As soon as there are input/output events, unknown content at compile time, etc. - The block becomes invalid for comptime. Sometimes it can be a challenge to make the code fully independent of the runtime. In this case, true random numbers can't be generated at compile time, but we use a trick to make it look like they don’t follow a mathematical progression.

setEvalBranchQuota

The compiler has built-in limits to prevent comptime evaluations from running too long. That’s why we’re using the instruction:

|

@setEvalBranchQuota(2000); |

This increases the compile-time evaluation limit. Without this instruction, the compiler throws an error:

|

pins.zig:17:40: error: evaluation exceeded 1000 backwards branches a_pins[n_i] = get_pin4index(n_i); ~~~~~~~~~~~~~^~~~~ |

The error indicates that the compile-time evaluation exceeds the default limit for backward branches. This is a safeguard the compiler uses against infinite loops or excessive evaluations; in our case, it has detected too many iterations, so it decides to abort the mission.

We increase the number to 2,000 because we know the formula we’re using is safe, and we can clearly see that we need 1,000 full iterations to generate the PINs. It’s not just our visible iterations that count - internal execution branches also add up: function calls, condition checks, safety validations, etc. 2,000 might seem high to the compiler, but it’s manageable as long as we know what we’re doing and make it explicit.

If you’re not sure about the exact value needed for @setEvalBranchQuota, you can start with a conservative estimate - roughly double your visible iterations - and increase it if necessary. If you get it wrong, the compiler will complain.

You might think: why not just set a very high value and forget about it? The “danger” of using an excessively high number isn’t that your program will run worse - in fact, once compiled, this number has no effect on performance. But doing it this way isn’t good practice: it could hide near-infinite loops by accident, unnecessarily extend compile times, and make your code harder to maintain. Besides, knowing what you're doing is key to building things that work well.

PINs as strings

To use the generated numbers as PINs, they must be 6 digits long. That means we must send them as strings - for example, 1 should be sent as 000001. We also have to consider that strings like 000001, 000002, etc., are easily guessed in an automated attack, so we’ll start from a higher index defined in the constant N_START.

So, we proceed to convert them into strings:

pins_strings.zig |

|

const std = @import("std"); const print = std.debug.print; // get a PIN for an index fn get_pin4index(n_x: usize) usize { const n_a = n_x + 1; // pentagonal number formula return (n_a * (3 * n_a - 1)) / 2 % 1_000_000; } // convert the number to a zero-padded string fn left_pad_zeros(n_a: usize, n_len: usize) [n_len]u8 { comptime var s_resp: [n_len]u8 = undefined; for (0..n_len) |n_ix| { s_resp[n_ix] = '0'; } var n_x: usize = n_a; if (n_x == 0) return s_resp; for (0..s_resp.len - 1) |n_i| { const n_pos = s_resp.len - 1 - n_i; const n_digit = n_x % 10; s_resp[n_pos] = @as(u8, '0' + n_digit); n_x = n_x / 10; } return s_resp; } // declare the maximum PIN length const N_PIN_LENGTH = 6; // start the series at slightly higher numbers const N_START = 100; pub fn main() void { comptime var a_pins: [1000][N_PIN_LENGTH]u8 = undefined; comptime { // at compile time: // we have at least 1000 * (6 + 6) = 12000 visible iterations // 1000 from the for loop and (6 + 6) from left_pad_zeros // plus ~2000 from the previous example = 14000 @setEvalBranchQuota(14000); for (0..a_pins.len) |n_i| { // get the PIN based on the index const n_pin = get_pin4index(n_i + N_START); // convert the PIN to a zero-padded string a_pins[n_i] = left_pad_zeros(n_pin, N_PIN_LENGTH); } } // print the first 5 // and last 5 PINs to check the result for (a_pins[0..5].*, 0..) |s_pin, n_i| { print("a_pins[{}]: {s}\n", .{ n_i, s_pin }); } print("...\n", .{}); const n_last = a_pins.len; for (a_pins[n_last - 5 .. n_last].*, n_last - 5..) |s_pin, n_i| { print("a_pins[{}]: {s}\n", .{ n_i, s_pin }); } } |

|

$ zig run pins_strings.zig |

|

a_pins[0]: 015251 a_pins[1]: 015555 a_pins[2]: 015862 a_pins[3]: 016172 a_pins[4]: 016485 ... a_pins[995]: 001276 a_pins[996]: 004565 a_pins[997]: 007857 a_pins[998]: 011152 a_pins[999]: 014450 |

Now this is the correct format for a PIN.

Whoever coined the Spanish saying that something or someone is “cero a la izquierda” (“a zero to the left” - meaning they don’t count for anything) didn’t know that one day passwords and PINs would take the value of those zeros seriously. At least their ASCII value: 48, to be exact.

If you look closely, you’ll see how the last PINs return to lower values. The “% 1_000_000” modulo makes the numbers “wrap around” once they exceed 6 digits and go back to lower values. In other words, we keep only the last 6 digits, regardless of the number's size. This also makes the PINs less predictable.

Simple permutation

Now, as the final step in generating our series of “unpredictable” PINs, we’re going to shuffle them a bit - but since this happens at compile time, it will still be a deterministic shuffle.

This way, even though the series was generated through several deterministic steps, it’s not so easy to figure out what those steps were just by looking at the final result.

pins_permuted.zig |

|

const std = @import("std"); const print = std.debug.print; // get a PIN for an index fn get_pin4index(n_x: usize) usize { const n_a = n_x + 1; // pentagonal number formula return (n_a * (3 * n_a - 1)) / 2 % 1_000_000; } // convert the number to a zero-padded string fn left_pad_zeros(n_a: usize, n_len: usize) [n_len]u8 { comptime var s_resp: [n_len]u8 = undefined; for (0..n_len) |n_ix| { s_resp[n_ix] = '0'; } var n_x: usize = n_a; if (n_x == 0) return s_resp; for (0..s_resp.len - 1) |n_i| { const n_pos = s_resp.len - 1 - n_i; const n_digit = n_x % 10; s_resp[n_pos] = @as(u8, '0' + n_digit); n_x = n_x / 10; } return s_resp; } fn get_permuted_index(n_i: usize, n_items: usize) usize { // simple deterministic seed return (n_i * 524287) % n_items; } // declare the maximum PIN length const N_PIN_LENGTH = 6; const N_START = 100; // declare the total number of PINs created const N_TOTAL_PINS = 1000; pub fn main() void { comptime var a_pins: [N_TOTAL_PINS][N_PIN_LENGTH]u8 = undefined; comptime { // add 1000 more for the call to get_permuted_index @setEvalBranchQuota(15000); for (0..a_pins.len) |n_i| { // get the PIN based on the index const n_pin = get_pin4index(n_i + N_START); // get a new position in the array const n_pos = get_permuted_index(n_i, N_TOTAL_PINS); // convert the PIN to a zero-padded string a_pins[n_pos] = left_pad_zeros(n_pin, N_PIN_LENGTH); } } // print the first 5 // and last 5 PINs to check the result for (a_pins[0..5].*, 0..) |s_pin, n_i| { print("a_pins[{}]: {s}\n", .{ n_i, s_pin }); } print("...\n", .{}); const n_last = a_pins.len; for (a_pins[n_last - 5 .. n_last].*, n_last - 5..) |s_pin, n_i| { print("a_pins[{}]: {s}\n", .{ n_i, s_pin }); } } |

|

$ zig run pins_permuted.zig |

|

a_pins[0]: 015251 a_pins[1]: 012210 a_pins[2]: 015792 a_pins[3]: 028497 a_pins[4]: 000825 ... a_pins[995]: 047301 a_pins[996]: 022145 a_pins[997]: 097612 a_pins[998]: 027702 a_pins[999]: 066915 |

As you can see, the order of the PINs has changed, even though the content is the same.

We used a simple principle to perform the permutation:

- Given an index I, if we multiply I by a large number P and then apply % 1000 (modulo 1000), we get a very large number and keep only its last three digits.

- If

is an index in the PINs array, which has 1000 elements (that’s why we do %

1000), the result of this operation - no matter the value of

is an index in the PINs array, which has 1000 elements (that’s why we do %

1000), the result of this operation - no matter the value of  - will be a number in the range 0 to 999. (Naturally, 0 won’t change since 0 * P % 1000 = 0).

- will be a number in the range 0 to 999. (Naturally, 0 won’t change since 0 * P % 1000 = 0). - The larger P is, the larger the result of the multiplication. If the result is a 12- or 20-digit number, the last three digits - which we care about - will be much more diverse throughout the sequence than if the result were only a 4-digit number, where we’d be drawing that final portion from just 75% of its “digit capital”.

- Our goal is to compute the result of this operation for each index:

) % N

) % N

In our case:

) % 1000

) % 1000

And just like that, we have permuted indices - the values are no longer in their original positions. Great job!

Ahem. It’s simple… but not that simple. There’s one more thing to keep in mind.

If you pick just any large number - say, 123456780 as P (yes, many people type “random” numbers that way, just following the keys) - you’ll run into a flaw in this approach: our array will be a mess. The result will start repeating, causing collisions (overwriting the same index) and leaving gaps (positions left unassigned).

We’re missing a key detail.

Let’s take a look at the number N, which in our case is 1000:

1000 = 10³

10³ = 2³ * 5³

Now let’s look at P = 123456780:

123456780 / 2 = 61728390

123456780 / 5 = 24691356

Our number P shares factors with 1000: both 2 and 5.

To make sure this doesn’t happen, we need the greatest common divisor (GCD) of N and P to be 1.

- “But… does that even exist?”

- Yes. If that’s the case, math tells us that N and P are coprime.

- “How do we find such a number?”

The most straightforward way is to use numbers you’ve probably heard of - called prime numbers in math. These are numbers divisible only by 1 and themselves.

Luckily, you can just pick them from a pre-made list. There’s no need to calculate them yourself. In fact, one of the great challenges in mathematics is finding extremely large prime numbers - something that wouldn’t be possible without programming.

If we use a large prime number like 524287 as P - a prime with some fame, prestige, and a Mersenne surname, inherited from the great mathematician who studied it (and who you should definitely look up later) - we get a value divisible by 524287, by the index I, and by 1. But the key point is that it shares no factors with 1000.

You can verify that 524287 divided by 2 or 5 does not yield an integer.

So, when we have an index I in the range 0 to 999, and we multiply it by 524287, then apply % 1000 (with 524287 and 1000 being coprime), here’s what happens:

- The result will naturally fall between 0 and 999 (we’re keeping the last three digits),

- But more importantly, the result will never be equal to the original I, except when I = 0.

- And the most important part: all indices will be covered without any repetition.